Patient Consent vs Data Ownership: A Critical Gap in Digital Health

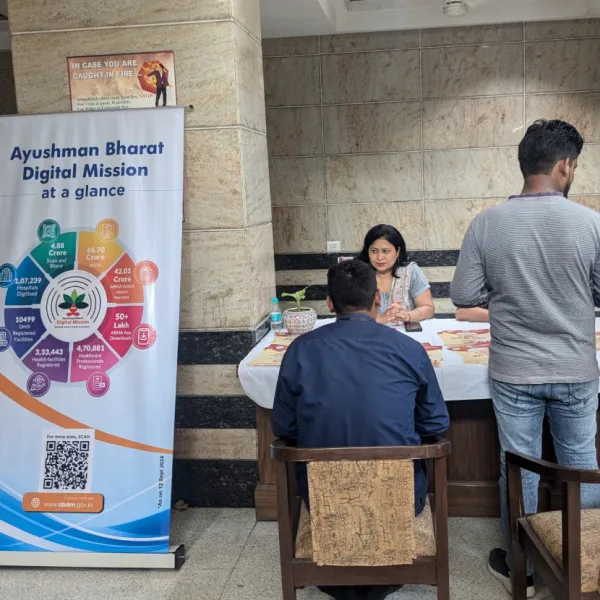

The digital age has significantly made healthcare increasingly data-driven. While digital tools have potient to strengthen care, interoperability, and research, however, it raises complex questions regarding patient consent and patient data ownership. In India, digital health missions such as ABDM have positioned data as a critical asset of healthcare delivery. Though these developments improved continuity of care and efficiency of the healthcare system, the concerns regarding healthcare data privacy have also become critical.

In this regard, the distinction between patient consent and data ownership becomes central. Although consent-based data processing is increasingly institutionalised in Indian healthcare, the concept of ownership of health data remains legally ambiguous, raising important ethical, legal, and operational questions. This article explores the conceptual, legal, and practical differences between patient consent and data ownership in Indian healthcare.

Understanding Key Concepts

Patient Consent

Patient consent is defined as an individual's voluntary, informed, and explicit approval to the gathering, processing, or sharing of their health data for a particular purpose. Consent, which has historically been connected to clinical decision-making, has broadened in the digital age to include data transfers between insurers, researchers, healthcare providers, and digital health platforms. Consent serves as the main legal justification for processing personal data, including health data, under India's new data protection laws, especially the Digital Personal Data Protection (DPDP) Act, 2023.

Data Ownership

Data ownership, by contrast, denotes rights over health data, including authority over access, reuse, retention, and secondary applications such as research or analytics. Ownership implies control beyond initial consent, allowing individuals to determine how their data is used over time

Under proposals like the Digital Information Security in Healthcare Act (DISHA) draft, data collected by clinical establishments can only be used with the express consent of the data owner, and custodians have an obligation to protect it.

However, health data ownership is not explicitly defined in the current statutory law. Instead, patients are recognised as data principals, while hospitals, laboratories, insurers, and digital health platforms act as data custodians responsible for secure storage and lawful processing.

Patient Consent vs Data Ownership in Practice

India’s digital health governance framework illustrates the practical tension between patient consent and data ownership through its evolving regulatory framework. Early policy approach such as DISHA, had explicitly recognized patients as the owners of their health data and imposed stringent restrictions on its commercial use. In contrast, the National Digital Health Blueprint placed less focus on ownership rights and more emphasis on the development of a federated digital health ecosystem through health IDs, registries, and interoperable data-sharing infrastructure.

The divergence from this became more evident with the enactment of the Digital Personal Data Protection Act 2023, which adopts a sector-agnostic framework focused on lawful data processing through consent rather than explicit recognition of ownership.

While this shift facilitates expanded data use and operational flexibility for healthcare institutions and digital platforms, it also weakens patient control over secondary and commercial uses of health data. The patient's capacity to maintain control may be reduced by secondary uses of health data, such as clinical research, public health surveillance, or health system analytics, which may be permitted only by broad consent clauses or legal exemptions.

This strategy provides operational freedom for digital health platforms and healthcare providers, but it also creates confusion about acceptable data use. Accountability for data breaches, misuse, and economic exploitation is complicated by the lack of well-defined ownership rights. Furthermore, the efficacy of permission as a significant precaution may be compromised by disjointed consent procedures and inadequate patient digital literacy.

Although national frameworks such as ABDM attempt to address these challenges by enabling standardised, revocable digital consent for health data sharing, these systems still operate within a consent-centric paradigm and do not resolve fundamental questions of ownership, such as long-term data control, deletion rights, or benefit-sharing from data-driven innovation.

Conclusion

The distinction between patient consent and data ownership is central to India’s evolving digital health ecosystem. While the current framework provides a necessary legal foundation for data management, however, they are insufficient to guarantee individual autonomy over health records. The lack of clear guidance regarding data ownership raises ethical and legal significant concerns for patients’ health data privacy. The limited control over data ownership may affect patients’ trust in the healthcare system potiently affecting patient outcomes. Therefore, balancing collective benefits with individual autonomy remains a central challenge in health data governance.

Stay tuned for more such updates on Digital Health News