Breath-Based Device Detects Diabetes Faster than Blood Tests

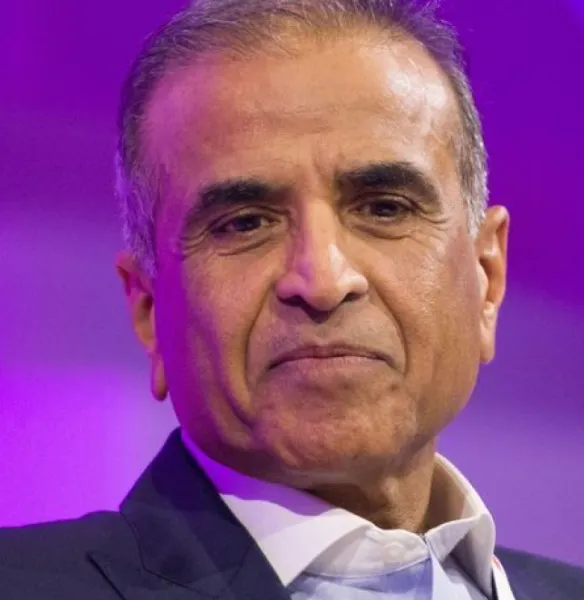

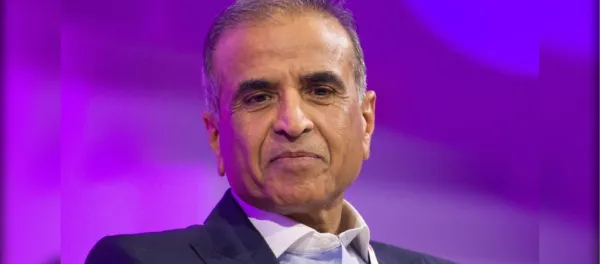

Although acetone occurs naturally as a byproduct of fat metabolism, concentrations higher than around 1.8 parts per million are a strong indicator of diabetes.

A team of scientists at Penn State has created a breath sensor capable of identifying diabetes by detecting acetone. The device is designed to be quick, non-invasive, and uses laser-induced graphene for high precision.

In the United States, nearly one in five of the 37 million adults living with diabetes is unaware of their condition. Conventional diagnostic methods often require clinical visits and laboratory tests, which can be both expensive and time-consuming. The new research suggests that detection could soon be as simple as analyzing a person’s breath.

Led by Huanyu “Larry” Cheng, the James L. Henderson, Jr. Memorial Associate Professor of Engineering Science and Mechanics at Penn State, the team has developed a sensor that can diagnose diabetes and prediabetes within minutes using only a breath sample. The findings were published in the Chemical Engineering Journal.

Traditional diagnostic approaches have typically focused on glucose levels in blood or sweat, but this new sensor targets acetone in exhaled breath. Although acetone occurs naturally as a byproduct of fat metabolism, concentrations higher than around 1.8 parts per million are a strong indicator of diabetes.

“While we have sensors that can detect glucose in sweat, these require that we induce sweat through exercise, chemicals, or a sauna, which are not always practical or convenient,” Cheng said. “This sensor only requires that you exhale into a bag, dip the sensor in, and wait a few minutes for results.”

Cheng explained that earlier breath-analysis devices often targeted biomarkers needing laboratory confirmation. The new design, however, enables on-site acetone detection, making it both practical and cost-effective.

Beyond identifying acetone as a key biomarker, the innovation lies in the sensor’s structure and materials, particularly the use of laser-induced graphene. The material is produced by exposing a carbon-based substrate, such as polyimide film, to a CO₂ laser, which transforms it into a patterned, porous graphene.

“This is similar to toasting bread to carbon black if toasted too long,” Cheng said. “By tuning the laser parameters such as power and speed, we can toast polyimide into few-layered, porous graphene form.”

The researchers combined laser-induced graphene with zinc oxide to increase acetone selectivity. “A junction formed between these two materials that allowed for greater selective detection of acetone as opposed to other molecules,” Cheng said.

One challenge the researchers faced was breath humidity. Since water molecules could interfere with acetone detection, they added a selective membrane that blocks water but allows acetone to pass through.

Currently, the method requires users to exhale into a bag to prevent airflow interference. Cheng said the next goal is to improve the sensor for direct use under the nose or within a mask, where it could analyze exhaled condensation.

“If we could better understand how acetone levels in the breath change with diet and exercise, in the same way we see fluctuations in glucose levels depending on when and what a person eats, it would be a very exciting opportunity to use this for health applications beyond diagnosing diabetes,” Cheng said.

The study, titled “ZnO/LIG nanocomposites to detect acetone gas at room temperature with high sensitivity and low detection limit,” was published on June 13, 2025, in the Chemical Engineering Journal. The work was supported by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

Stay tuned for more such updates on Digital Health News